Each patient has a story to tell...

. . . in time you learn to deal with it

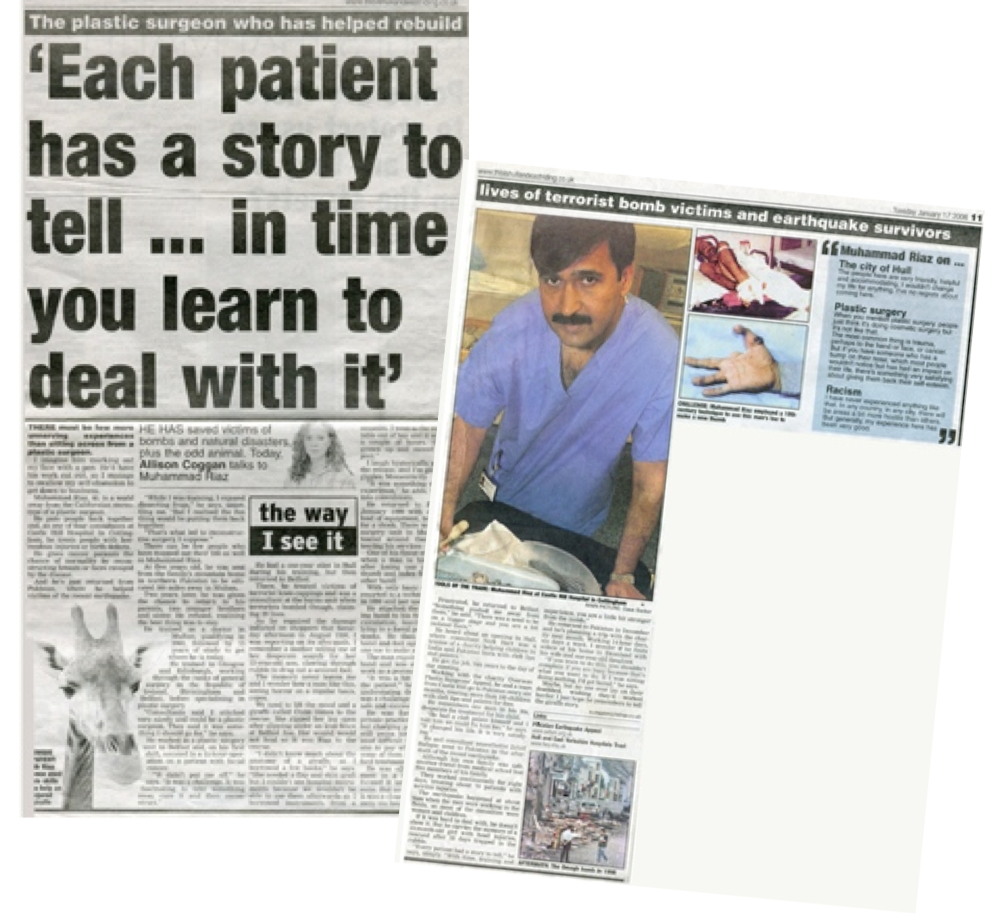

He has saved victims of bombs and natural disasters, plus the odd animal. Today Allison Coggan talks to Mr Muhammad Riaz.

There must be few more unnerving experiences than sitting across from a plastic surgeon.

I imagine him marking out my face with a pen. He’d have his work cut out, so I manage to swallow my self-obsession to get down to business. Muhammad Riaz, 46, is a world away from the Californian stereotype of a plastic surgeon. He puts people back together and, as one of four consultants at Castle Hill Hospital in Cottingham, he treats people with horrendous injuries or birth defects. He gives cancer patients the chance ‘of normality by reconstructing breasts or faces ravaged by the disease. . . And he’s just returned from Pakistan, where he helped victims of the recent earthquake. “While I was training, I enjoyed dissecting frogs,” he says, unsettling me. “But I realised the fun thing would be putting them back together. “That’s what led to reconstructive surgery, I suppose.”

There can be few people who have mapped out their life as’ well as Muhammad Riaz. At five years old, he was sent ‘from the family’s mountain home in northern Pakistan to be educated 300 miles away in Multan. Two years later, he was given the chance to return to his’ parents, two younger brothers and sister. He refused, realizing the best thing was to stay. He trained as a doctor in Multan, qualifying in 1983, followed by 15 years of study to get where he is today. He trained in Glasgow, and Edinburgh, working through the ranks of general surgery in the Republic of Ireland, Birmingham and Belfast, before specialising in plastic surgery.

“Consultants said I stitched very nicely and could be a plastic surgeon. They said it was something I should go for,” he says. He worked in a plastic surgery unit in Belfast and, on his first shift, assisted in a 15-hour operation on a patient with facial cancer. “It didn’t put me off,” he says. It was a challenge. It was fascinating to take something away, cure it and then reconstruct.”

He had a one-year stint in Hull during his training, but then returned to Belfast. There, he treated victims of terrorist knee-cappings and was a consultant at the burns unit when terrorists bombed Omagh, claiming 29 lives. As he repaired the damage inflicted on shoppers that Saturday afternoon in August 1998, I was reporting on its aftermath. I remember a mother telling me of her desperate search for her 12-year-old son, clawing through rubble to drag out a severed foot. The memory never leaves me and I wonder how a man like this, seeing horror on a regular basis copes.

We need to lift the mood and a giraffe called Oisin comes to the rescue. She ripped her leg open after slipping under an iron fence at Belfast Zoo. Her wound would not heal so it was Riaz to the rescue.

“I didn’t know much about-the anatomy of a giraffe, so I borrowed a few books,” he says. “She needed a flap and skin graft but I couldn’t use hospital instruments because we wouldn’t be able to use them afterwards so I borrowed instruments from a museum. I went to the zoo, made a table out of hay and it was over in a couple of hours. She’s now grown up and moved to Liverpool.” I laugh hysterically, grateful for the release, and I’m glad when he giggles. Momentarily. “It was something of a special experience,” he adds, sending me into convulsions.

He returned to Pakistan in January 1999 with a container load of equipment, but he was in for a shock. There was no plastic surgery unit in Multan and he toured around theatres, volunteering his services – unpaid. One of his finest moments came when a man in his 30s arrived after losing one arm and the thumb and index finger from his other hand. With only basic equipment, he resorted to a technique pioneered in 1898 and last used in 1940. He attached the man’s remaining hand to his foot, to maintain circulation, leaving the patient lying in a foetal position for three weeks. He then separated the hand and foot again and attached one toe to make a thumb. The man regained the use of his hand and was able to return to work as a postman. “It was a bit inconvenient for the patient,” he says, somewhat understating the matter. “But it was a challenge to come up with a safe and successful solution.”

He was forced to resort to private practice at night to get by; but charging patients in Pakistan still pains him. “That was the most difficult thing, asking someone to pay when you know how some of them had struggled to afford treatment.” He was offered a dingy basement in a hospital and transformed it into a plastic surgery suite. But no opportunities came.

It was a closed shop and he’d been away too long. Frustrated, he returned to Belfast. “Something pushed me away from there,” he said. “There was a need to be on a bigger stage and you are a bit isolated there.”

He heard about an opening in Hull, where consultant Nick Hart was a trustee of a charity helping children in India and Pakistan-born with cleft lips and palates. . He got the job, two years to the day of our meeting.

Working with the charity Overseas Plastic Surgeons’ Appeal, he and a team from Castle Hill go to Pakistan every six months, treating more than 100 children with cleft lips and palates for free. He remembers one man in his 30s, desperate for treatment for his child. “He had a cleft palate himself and I told him we could fix him too,” he says. “It changed his life. It is very satisfying.”

He and consultant anaesthetist Zahid Rafique went to Pakistan in the aftermath of the recent earthquake. Although his own family was safe, another friend from medical school lost five members of his family. They worked continuously for eight days, treating about 70 patients with terrible injuries. The earthquake happened at about 9am when the men were working in the fields, so most of the casualties were women and children. If it was hard to deal with, he doesn’t show it. But he carries the memory of a l3-month-old girl with head injuries, rescued after 10 days trapped in the rubble. “Every patient had a story to tell,” he says, simply. ” With time, training and. experience, you are a little bit stronger from the inside.” He returned to Pakistan in December and he’s planning a trip with the charity next month.

Working 14-hour days, six days a week, I wonder if he finds solace at his home in Swanland with his wife and one-year-old daughter. “If you train to do this, you shouldn’t complain if you are busy because that’s what you want to do. If I was sitting doing nothing, I’d get bored,” he says. Maybe, but no one ever lay on their deathbed, wishing they’d worked harder. I just hope he remembers to tell the giraffe story.